Originally published in: Gizmodo.com

From the Smurfs to the Wicked Witch of the West, our favorite stories contain an amazing number of silly hats. And these haven’t just sprung into existence thanks to drunk costume designers, but come from history — be it military or millinery. Here are 10 ridiculous hats that were incredibly important in the past.

10. The “Princess Hat” Was Based On The Headdress Of Mongolian Royalty

10. The “Princess Hat” Was Based On The Headdress Of Mongolian Royalty

The hennin is probably not a word you know, but it is a hat you’ve seen. The big picture above is full of women wearing a hennin. If you google “princess hat” you’ll get nothing but pictures of hennins. It’s the ridiculous cone-hat-with-piece-of-fabric that noble ladies apparently spent their days balancing on their head. There are variations. Some hennins are branched into two pieces, some are shaped more like flower pots than cones, and some have the veils coming out of the bottom. But they’re all probably based on the Mongolian boqta.

Worn by noble women, when they weren’t out fighting, the boqta was up to four feet tall. It was described, admiringly, by explorers and delegates who visited the royal court. So when we see women in 14th century paintings wearing the gauzy contraptions, they’re doing the same thing little girls who wear the hennin today are doing. They’re pretending they’re a royal princess from a far-away land.

9. The Witches’ Hat Was Basically Code For “Evil Outsider”

If you want to know why the Wicked Witch of the West wore a hat like a serving platter with a cone on it, you’re going to have to settle for an ambiguous answer. There are a lot of different theories about why witch hats are shaped the way they are, but they all have one thing in common: they are all caricatures of outsiders. Some say that they are anti-Semitic stereotypes. In the 13th century, the Pope required all Jews to wear horned hats so no one would mistake them for Christians.

But also, in the 1700s, Quaker women who preached in public would wear tall hats that looked a little bit like the witches’ hats. In the Puritan society of the North American colonies, women who dared to preach found themselves very unwelcome — and in fact, that was one of the many kinds of disruptive behavior on the part of certain women that led to the Salem Witch Trials.

Neither of those hats are exactly the cone hats, but they weren’t supposed to be. The hideous, hunched, evil, screeching outsider is an exaggeration of those people. It’s an artist’s attempt to keep the basic look, while turning them into something both ridiculous and insidious. So the witch costumes today are probably a parody of racial and religious persecution from centuries past.

8. Pointy Crowns Are Meant To Show Us That Their Wearers Are Divine

These crowns aren’t really crowns. They’re meant to show that the wearer is a god, or a semi-god. There are plenty of depictions of this. Statues of Attis, a Greek semi-god who was the spawn of a nymph and a divine almond tree and later castrated himself when he gazed upon the goddess Cybele (don’t ask), often give him this kind of crown. Statues of Moses also get this, although Moses, being part of a monotheistic system, only get two horns on his crown. And, of course, we see this crown on the Statue of Liberty.

What we’re seeing is the sculptor’s best try at showing us a halo of light centering around the divine being’s head. We are meant to be dazzled by the radiant shafts of illumination. Instead we looked at these statues and thought, “That sure is a pretty crown. Let’s put it on King Triton.”

7. The Cap Of Maintenance Might Be A High Honor Or It Might Be A Head Warmer

So, in this picture of the 1911 Coronation of George V, you see the crowns themselves, the metal circlets and the high metal framework. Now do you see the inner part of the crown? It’s a round circle of spotted white ermine fur and what looks like a big velvet cream puff that conforms to the structure of the crown? That’s a separate part of the crown, and it’s called the cap of maintenance.

Traditionally, kings wear the cap of maintenance on their way to be crowned. This is a tradition that goes, at the very least, back to Henry VIII. It’s said that the right to wear the cap was given to the kings by the Pope. It’s also said that it’s just a way to fit a rigid metal crown to a literal succession of different-sized heads, and also a way to keep those heads from chafing under the metal. Whatever the origin of the tradition, we often see these fur-lined velvet cream-puff hats on high officials in fantasy films or historical films. We have Henry VIII’s cap, because kings began giving out their caps to people as a very, very high honor. While it’s doubtful that anyone wore the king’s hat, many officials made imitations of the style. It became relatively common for high town officials to have red velvet hats with white spotted fur linings.

6. The Fez Was A Symbol Of Equality

The fez itself isn’t actually silly. As we see in these pictures, it’s unusual to modern eyes, but not ridiculous. Unfortunately the Shriners (an off-shoot of the Freemasons) did quite a lot of damages to its aesthetic reputation.

In the early 1800s, Sultan Mahmud II decided that he wanted to modernize the Ottoman Empire. He reorganized the army, discouraged religious dress, and eventually introduced the fez as the most acceptable (and sometimes only acceptable) form of headgear.

This was not entirely a good thing. Naturally, many people bridled at being told what to wear, especially since traditional dress soon carried the social stigma of being “primitive,” and unenlightened. Some people still look at his reforms as a way of forcing Westernization on people. However, his decrees did overturn sumptuary laws, which banned certain forms of dress, sometimes for religious reasons and sometimes to preserve a visible difference between the rich and the poor. The fez came to be seen, by some, at least, as a symbol of equality.

5. French Maids Wear Symbols Of Revolution On Their Heads

Think of every “sexy french maid” costume you’ve ever seen. There’s always a weird little lacy hat on her head, right? That’s called a “mob cap,” and it symbolizes a woman’s willingness to beat you to death with a garden rake, or just institute a system that leads to you being tried in an afternoon and beheaded. The mob cap got its name because the lower-class women, who worked in kitchens, factories, as maids and nurses, and generally anywhere it was important not to get their hair in their work, wore white hair-covering caps with a bit of a frill on them. When they went out into the streets to riot as a mob, they wore their caps.

Even before the Revolution, mob caps were in style. Writers like Rousseau made simplicity and nature and homeliness a fashion, and even upper-class women sometimes wanted to keep their hair out of their face. Their mob caps were heavy on silk, frills, and ruffles. The Revolution made these white caps even more fashionable, but, being French, decided they could use a little improvement. Mob caps shrank, both for ladies and for ladies’ maids, who were expected to look as fashionable as the rest of the house. So when we see tiny little maid hats, on Halloween or on the covers of steampunk novels, we’re seeing the last remnants of the French Revolution. (Technically, though, the hair-covering paper-like caps that nurses and doctors wear today can still be called mob caps.)

4. The Tinfoil Hat Debuted In An Obscure Short Story

In The Tissue Culture King, by Julian Huxley, a young explorer gets lost in a jungle and comes into contact with an entirely new civilization. The culture worships animals and ancestors, but instead of forms or bodies, it begins to worship living tissues. Through helping the tribe develop and maintain its sacred tissues, and participating in other experiments, the explorer comes to create a “tissue culture king,” who can control the entire culture through telepathy.

Guess what “greatly reduces” the effects of the telepathy on one’s brain? You got it. This story, published in 1927, introduced the concept of headgear made of aluminum foil to the public consciousness. It has since flourished as a way of marking people who were either wise to terrible world-wide mind-control experiments, or who just thought they were.

3. The Carpenter’s Hat Shows He Was A Real Tradesman

If you watch Disney’s Alice in Wonderland, the Walrus and the Carpenter sequence shows the Carpenter as a little man in what looks, at first, like the kind of paper hat people would wear if they were serving fast food at a fifties theme restaurant — the ones that look like an inverted paper boat. Look a little closer, and you see the that’s it’s a square hat. That’s Disney following the lead of the original illustrations in Carroll’s book.

This was a common tradesman’s hat. It was known as a printer’s hat, but it was worn by pretty much anyone who worked with their hands and had to keep their hair out of their eyes. It is as flimsy as it looks on screen. Just like fast food workers, the caps were made often out of spare paper, and then thrown away at the end of the day.

2. Robin Hood’s Hat Wasn’t Always As Simple As He Wears It

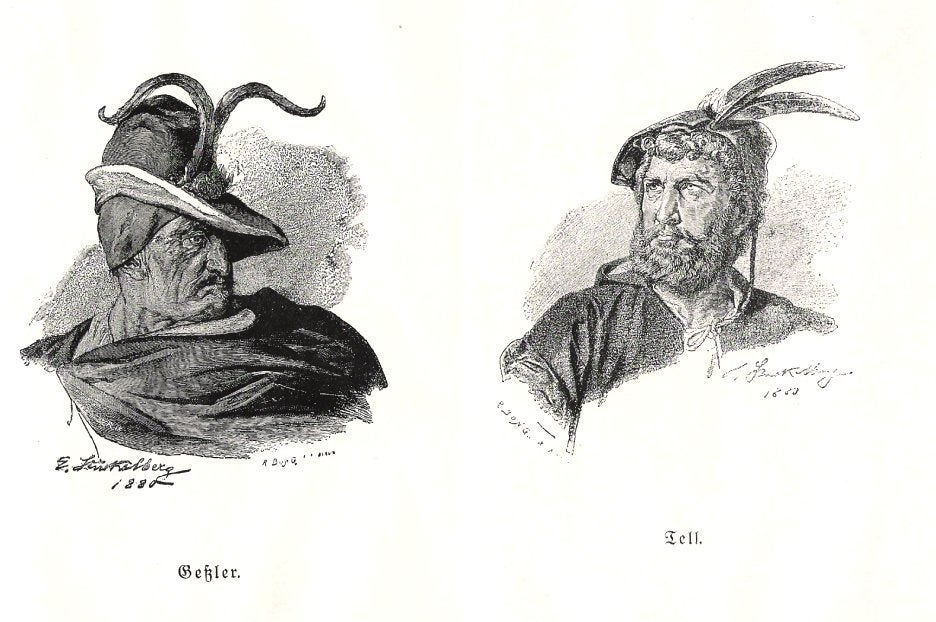

This is the hat that’s hardest to pin down. Most people know it as “the Robin Hood hat,” although it isn’t limited to the old Errol Flynn movies. The huntsman, in the animated Snow White movie wears a similar hat, as do some iterations of DC’s Green Arrow.

The best historical name for that kind of hat is the bycoket or chapel à bec. It’s not really a peasant hat, or

a simple hat. As you see in the illustration on the left, the only one wearing it is the guy on the fancy horse.

Still, the fact that, in the movies it was simply a roughly three-cornered felt hat with a single feather in is shows that Robin Hood was, relatively speaking, a man of the people. As you can see in the illustration above, there are ways to make the bycoket look very fancy indeed. If you do see it in movies, being worn either by Robin Hood or a bunch of aristocratic-looking men hunting with hounds, this hat keeps to its roots far more than the witch’s hat or the mob cap. It was worn as a hat that showed its wearer was both athletic and had a bit of style.

1. The Smurfs All Wear The Phrygian Cap

The headgear that we see the Smurfs wearing has a long, long history. Twenty-four hundred years ago, there are depictions of the cap. King Midas is often shown wearing one, because in one iteration of his legend he judges a playing contest between Apollo and Pan, sides with Pan, and is given donkey ears because he has the ears of an “ass.” He wears the cap to cover them up.

Later, the caps acquired a deeper significance. Legend has it that the Romans gave such a cap to their slaves when their slaves were freed. The cap became a symbol of liberty, especially when people started looking imitating classical styles. During the French Revolution, the revolutionaries would put on a red Smurf cap (often turned backwards) as a symbol that they wanted liberty. This earned them the nickname of the “bonnets rouges.” Want to see a bonnet rouge? Check out the seal of the US Senate, at left.

Although Smurf hats are undignified these days (because of the damn Smurfs), the people who designed the emblems of the United States had the pleasure of dying before the Smurf movies came out, and they were very into the symbolism of the phrygian caps. You’ll find “Smurf caps” worked into the old seal of the War Department, symbolizing that Americans will fight for physical liberty, and sculpted into the decorations on the Library of Congress, symbolizing the need for artistic and academic liberty.

Top Image: Boccaccio, The Fall of Princes